The 0.1% Problem: Why Your Shopify Review Score Probably Isn't What You Think It Is

This article explores why public review scores are often treated as a proxy for customer satisfaction — and why that assumption breaks down on most Shopify stores.

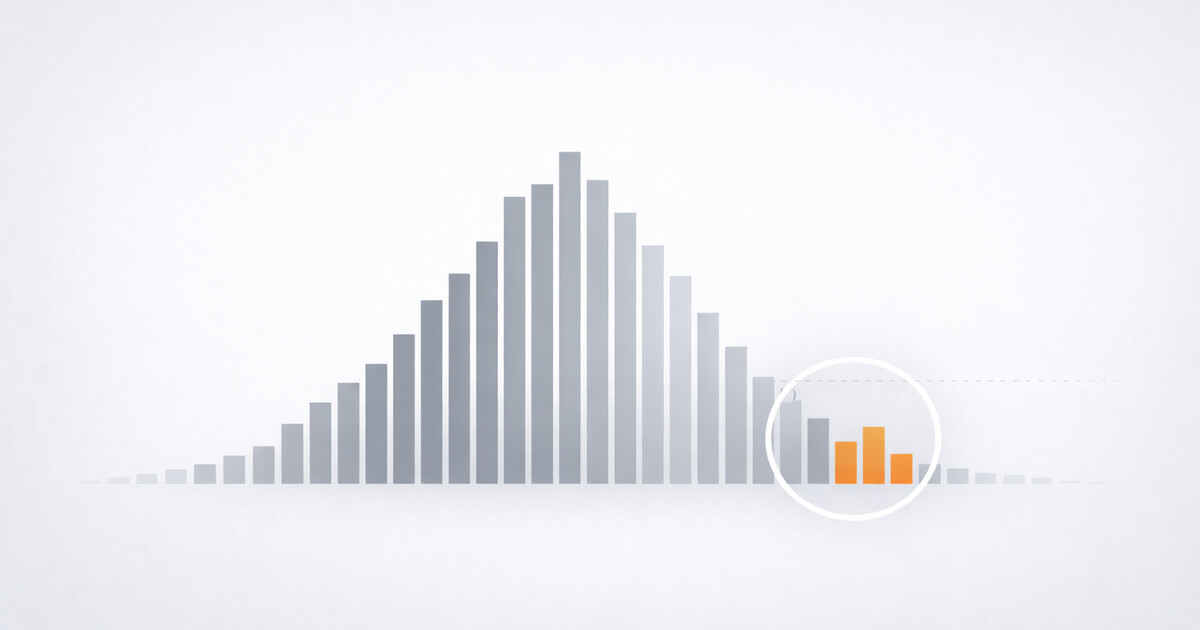

A typical Shopify store processes somewhere between 500 and 5,000 orders per month. The same store might display a public review score based on 30, 50, maybe 100 reviews in total. Depending on the store, that often represents less than one‑tenth of one percent of customers.

That score — 4.8 stars, 4.3 stars, whatever it is — is routinely treated as a reliable measure of customer satisfaction.

When we refer to a "Shopify review score", we mean the public ratings generated by third‑party review apps commonly used on Shopify stores.

But is it?

Why Review Scores Feel Authoritative

There's a reason star ratings carry weight. They look empirical. They aggregate opinion. They feel like data rather than anecdote.

The problem is that the sample they're drawn from is neither random nor representative.

Customers who leave reviews are disproportionately those who had an extreme experience — either exceptionally good or notably poor. The large middle group, who received broadly what they expected and moved on, typically says nothing at all.

This isn't a flaw in review platforms. Reviews were designed to provide social proof, surface edge cases, and give prospective customers confidence. They were not designed to function as statistically valid satisfaction surveys. The issue is that we increasingly treat them as if they were.

Time further degrades the signal. Reviews linger indefinitely. A complaint from eighteen months ago — long since resolved, tied to a supplier you no longer use or a process you've since fixed — still factors into the score customers see today. The number remains static, even as reality changes.

The Agency Exposure

For Shopify agencies, this creates a very specific kind of risk.

Agencies inherit a client's existing review profile. They implement change — a new checkout flow, a revised shipping policy, a different fulfilment partner, a reworked product mix. Some changes improve the experience immediately. Others introduce short‑term friction before stabilising.

Either way, the agency is now associated with a public metric it didn't design and cannot fully control.

When a public complaint appears, it is visible instantly. It doesn't matter that 400 other customers that week were perfectly satisfied. One negative review generates client anxiety, internal meetings, defensive explanations. The silent majority provides no counterweight.

Agencies are often judged on signals they didn't choose and can't properly manage.

A 4.9‑star store may have deeper satisfaction issues than a 4.5‑star store with healthier fundamentals — but there is no way to see that distinction from the score alone.

Reviews vs. Measurement

This is where the distinction matters.

Reviews are useful for marketing. They provide social proof, surface edge cases, and help customers set expectations. They are poor tools for measurement.

Measurement requires coverage. It requires asking the question consistently, across the whole customer base, in a way that captures the middle as well as the extremes. It requires separating genuine signal from performance theatre — optimising outcomes rather than optics.

Most review platforms do not do this because it is not what they were built for. They were built to display compelling testimonials and generate visible trust signals. That is a legitimate function. It is simply not the same thing as measuring customer satisfaction.

A Different Model

There is an alternative approach, though it requires a different way of thinking about feedback.

Instead of waiting for customers to voluntarily leave reviews, satisfaction is measured from every fulfilled order. Private feedback is separated from public display. What gets published is a store‑level signal that reflects overall customer sentiment, not a handful of self‑selected extremes.

This approach also creates space to address issues before they escalate. A customer who reports a poor experience can be engaged directly and privately, while the interaction is still fresh, before frustration turns into a public dispute. Problems are resolved earlier. The public signal reflects resolution, not just complaint.

It is a system designed for measurement first, marketing second.

Who This Is For

This model works best for brands with meaningful order volume — stores where statistical significance is actually achievable.

It suits merchants who care about signal quality rather than social‑proof hacks, and agencies managing long‑term client relationships where a misleading score can undermine otherwise effective work.

It is not designed for review farming or growth strategies built around gaming optics. It can still be valuable for operationally simple or high-churn models — including print-on-demand or dropship-style stores — where consistent measurement across every order often reveals improvements that traditional review scores fail to capture. Filtering by intent, rather than business model, increases the credibility of the signal.

Where This Comes From

We built StoreScore after repeatedly seeing this gap between public review scores and actual customer satisfaction.

The article isn't the product pitch. The product emerged from the problem. If the problem resonates, the solution tends to become obvious on its own.

The Question Worth Asking

Do you trust your review score as a measurement, or just as marketing?

And if you're an agency: how should you really be judged on customer satisfaction when the score you inherit represents only a tiny fraction of the customers you're actually serving?

For a fuller picture of why store ratings often don't represent the average customer experience, see why store ratings don't represent average customers.